Technology

Explore the innovative technology behind Luminous Photonics' horticultural lighting solutions, based on our Uniform Photon Flux Principle (UPFP) for modular LED arrays.

Luminous Photonics at a Glance:

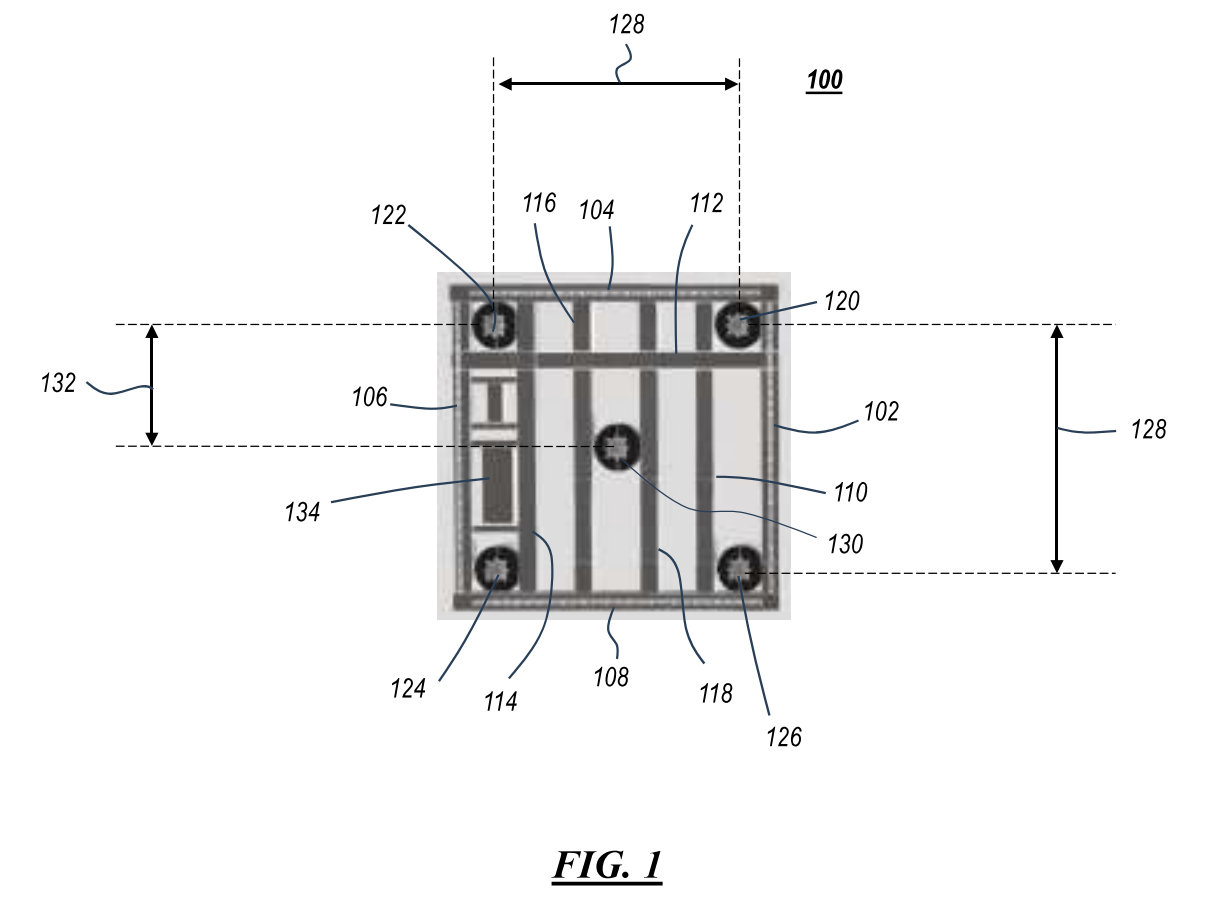

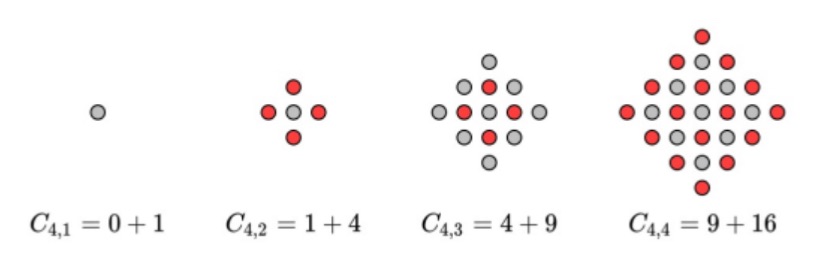

- Patented modular LED system based on centered-square logic

- Achieves >95% PPFD uniformity across any square/rectangular space

- Exceeds > 20% energy utilization rate versus leading commercial systems

- Fully scalable with 4 deployable lighting modules

Uniform Photon Flux Principle (UPFP)

Our research has led to the development of the Uniform Photon Flux Principle (UPFP), a groundbreaking approach to optimizing Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density (PPFD) distribution in controlled-environment agriculture. The UPFP leverages a particular arrangement of Chip-on-Board (CoB) LED elements, positioned according to the centered square number integer sequence (Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences: A001844) pattern logic. By carefully assigning optimal intensities to each layer, we achieve unprecedented uniformity in PPFD across the growing area.

Key Benefits of the UPFP:

- Enhanced Photosynthesis:

Uniform light distribution maximizes whole-canopy photosynthesis, leading to improved plant growth and yield (Zhang and Joshi et al., 2017). - Reduced Leaf Senescence:

Consistent light levels help slow down the aging process of leaves, prolonging their productive lifespan and preserving the vitality of lower leaves deep within the plant canopy, effectively solving the "light penetration" conundrum (Kozai, 2022). - Ideal for High-DLI Crops:

Particularly beneficial for crops that require high Daily Light Integral (DLI) for optimal growth (Runkle, 2021). - Energy Efficiency:

Optimized light distribution minimizes wasted energy, resulting in an energy utilization rate of > 20% when compared with leading competitors.

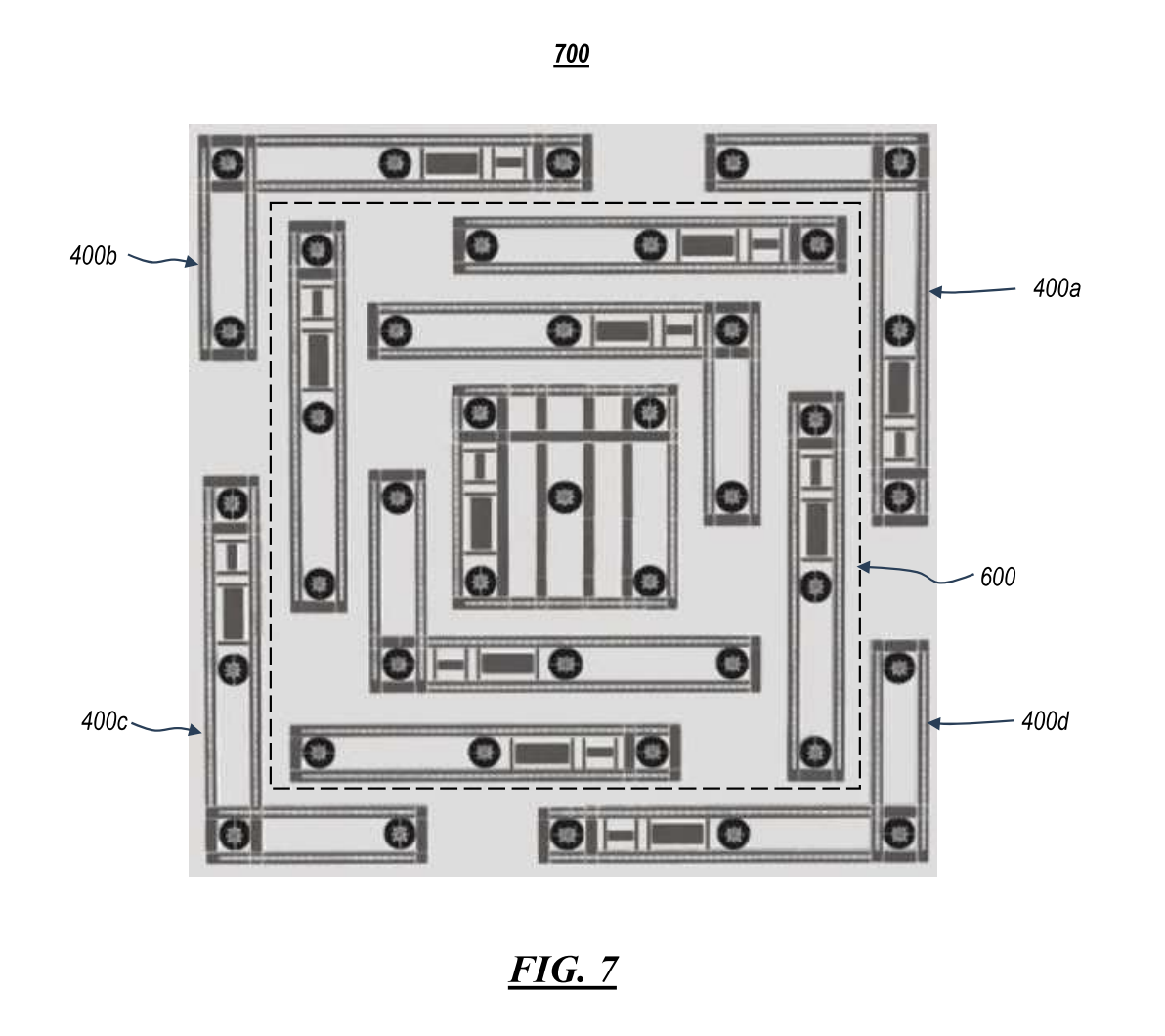

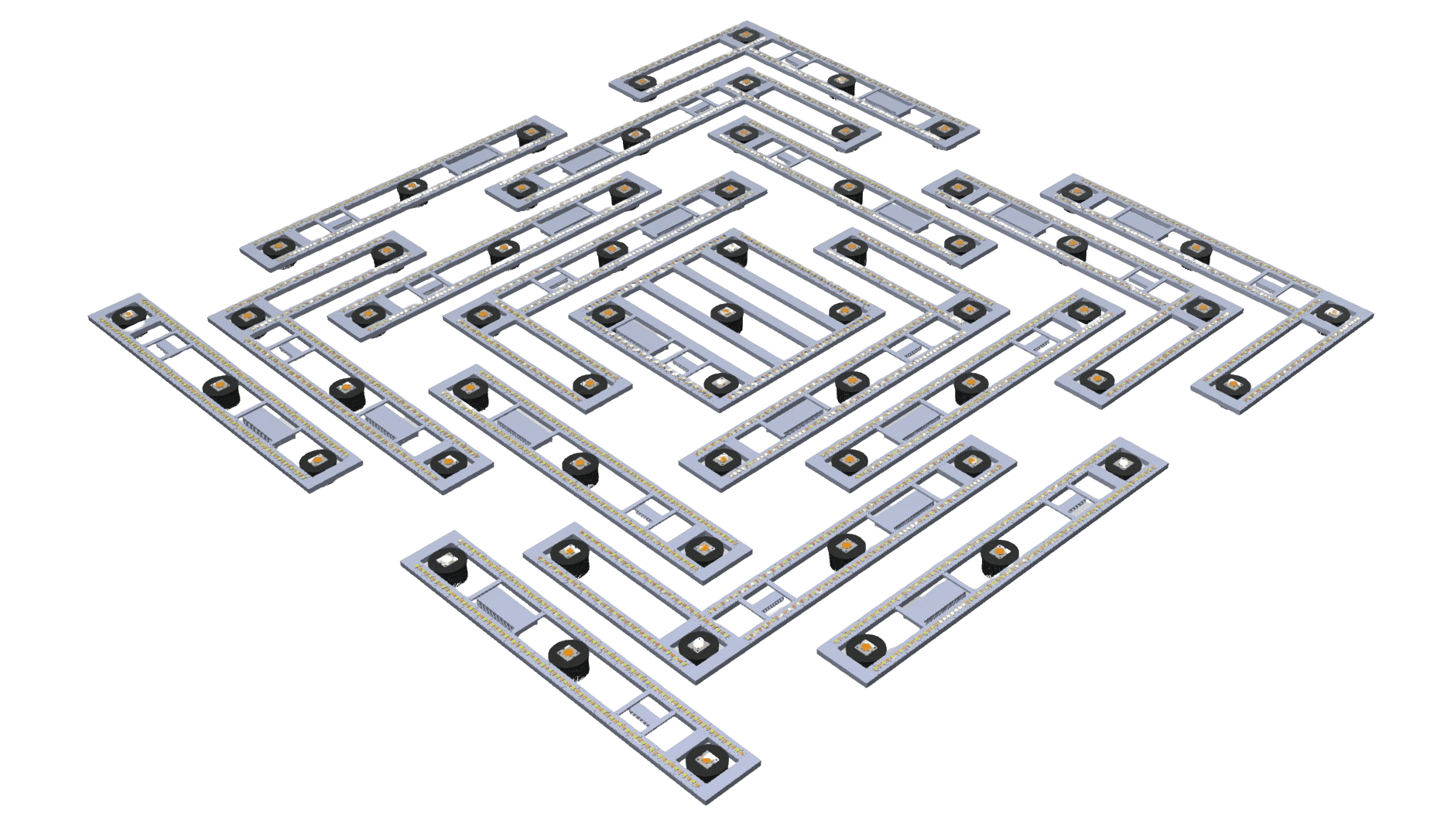

Infinitely Scalable Modularized System

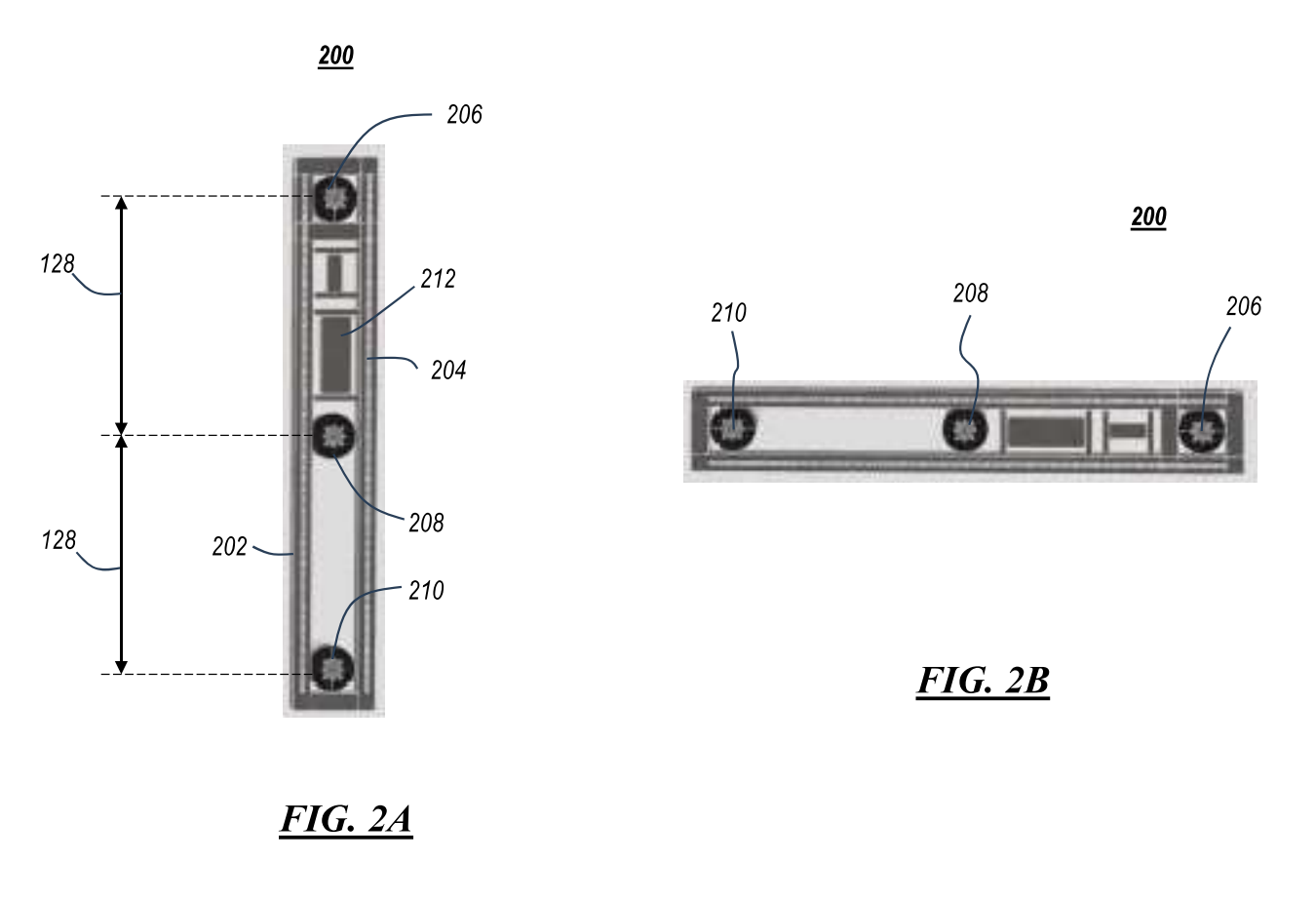

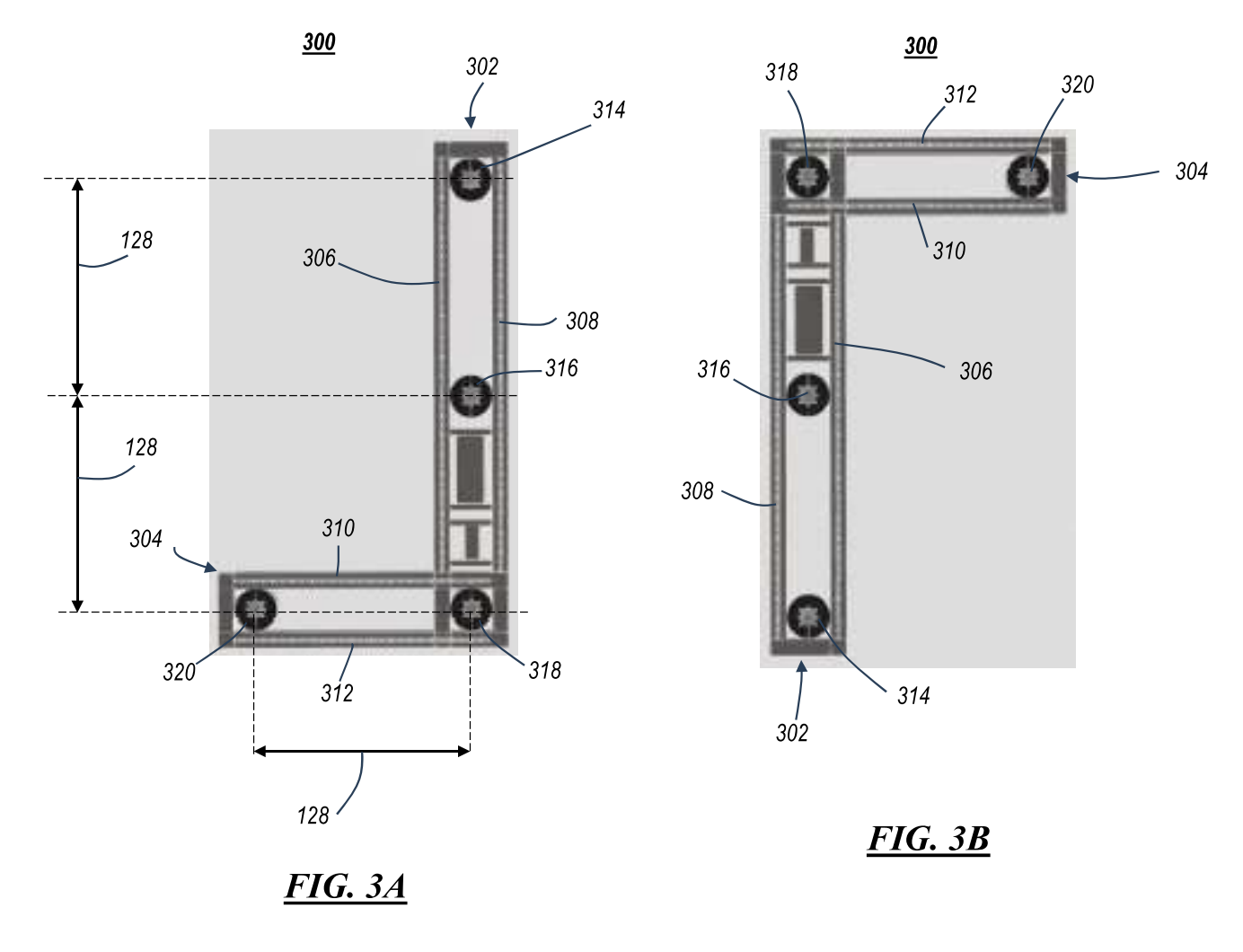

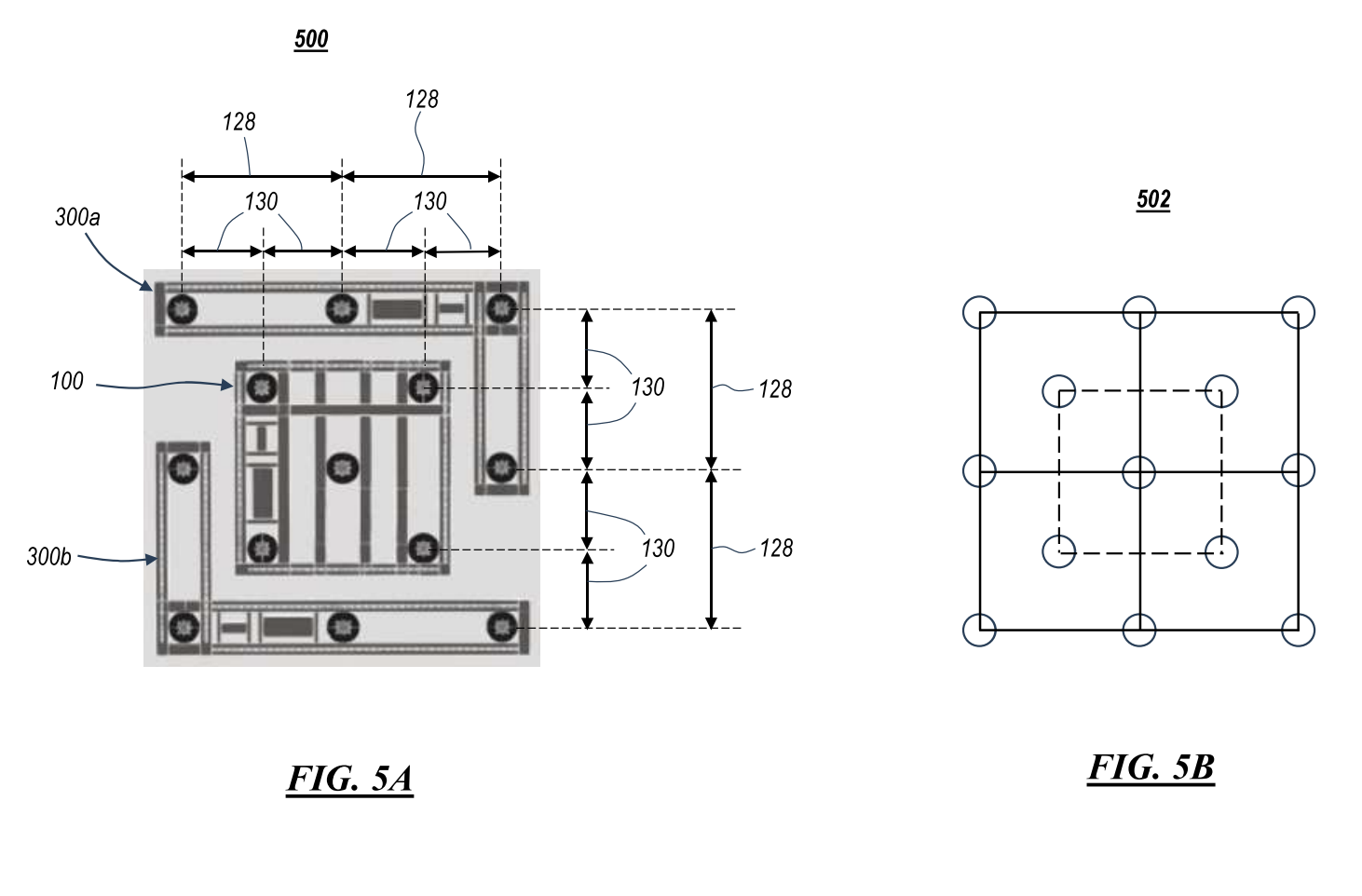

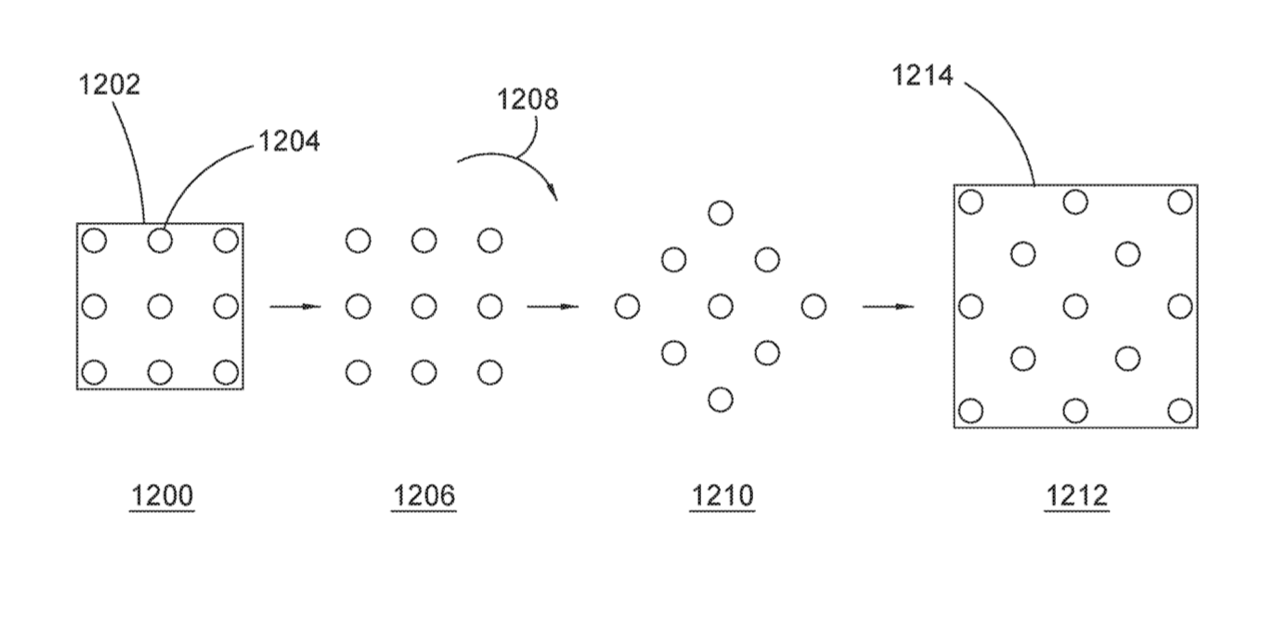

With just 4 types of modular pieces, our horticultural lighting system can optimally cover any size square or rectangular space.

Our arrangement strategem continues ad infinitum...

Infinite concentric square layers can be added to create endless configurations of arrays.

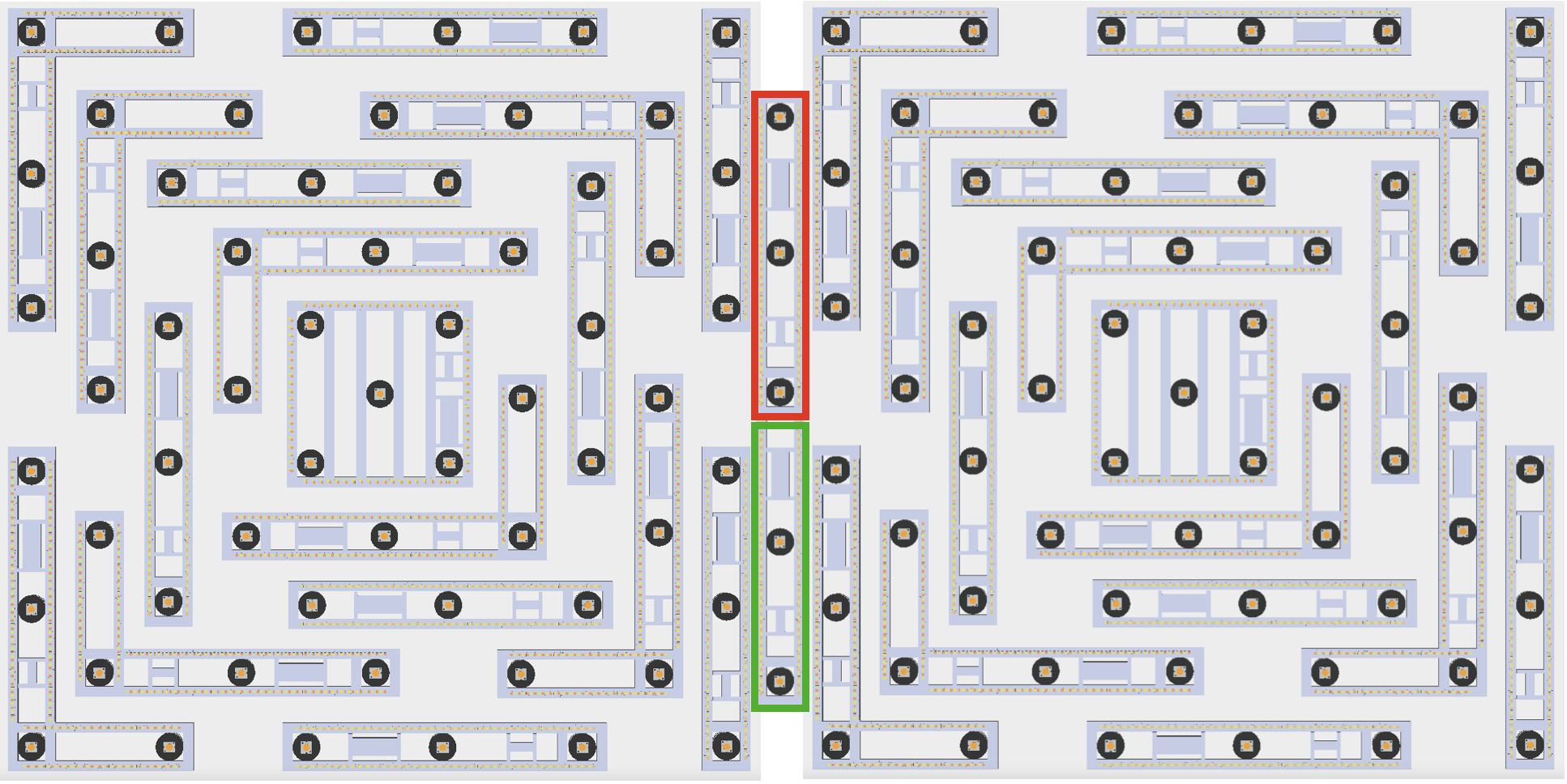

Here's an example of a 61-CoB lighting array.

And with just 2 linear connector modules, two square lighting arrays can be conjoined to form a perfect rectangular lighting array.

This system is protected by U.S. Patent 10,687,478 and a second patent pending — making Luminous Photonics the only lighting company to offer fully modular, layer-optimized COB lighting arrays for uniform PPFD delivery.

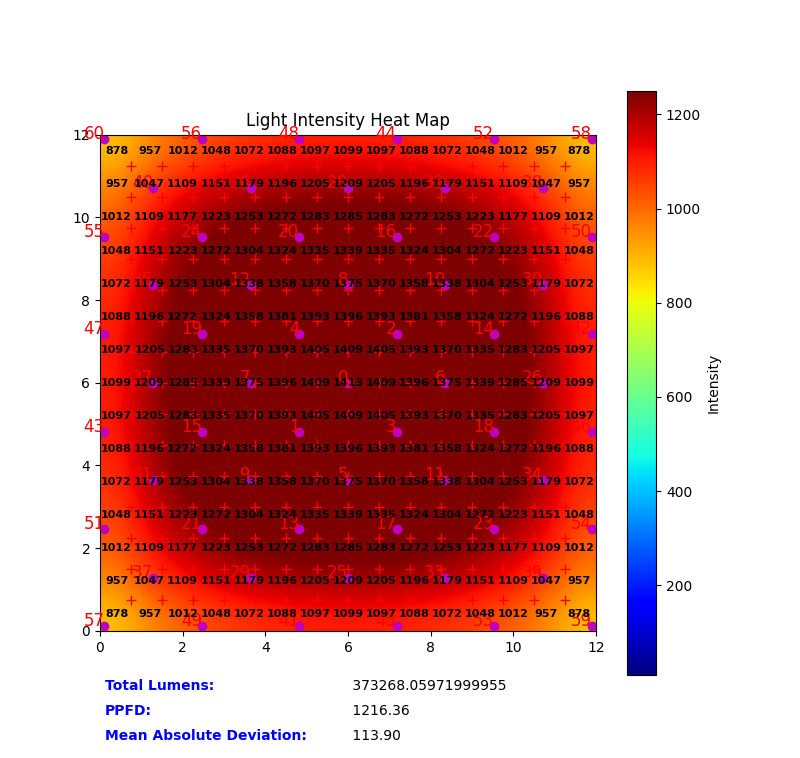

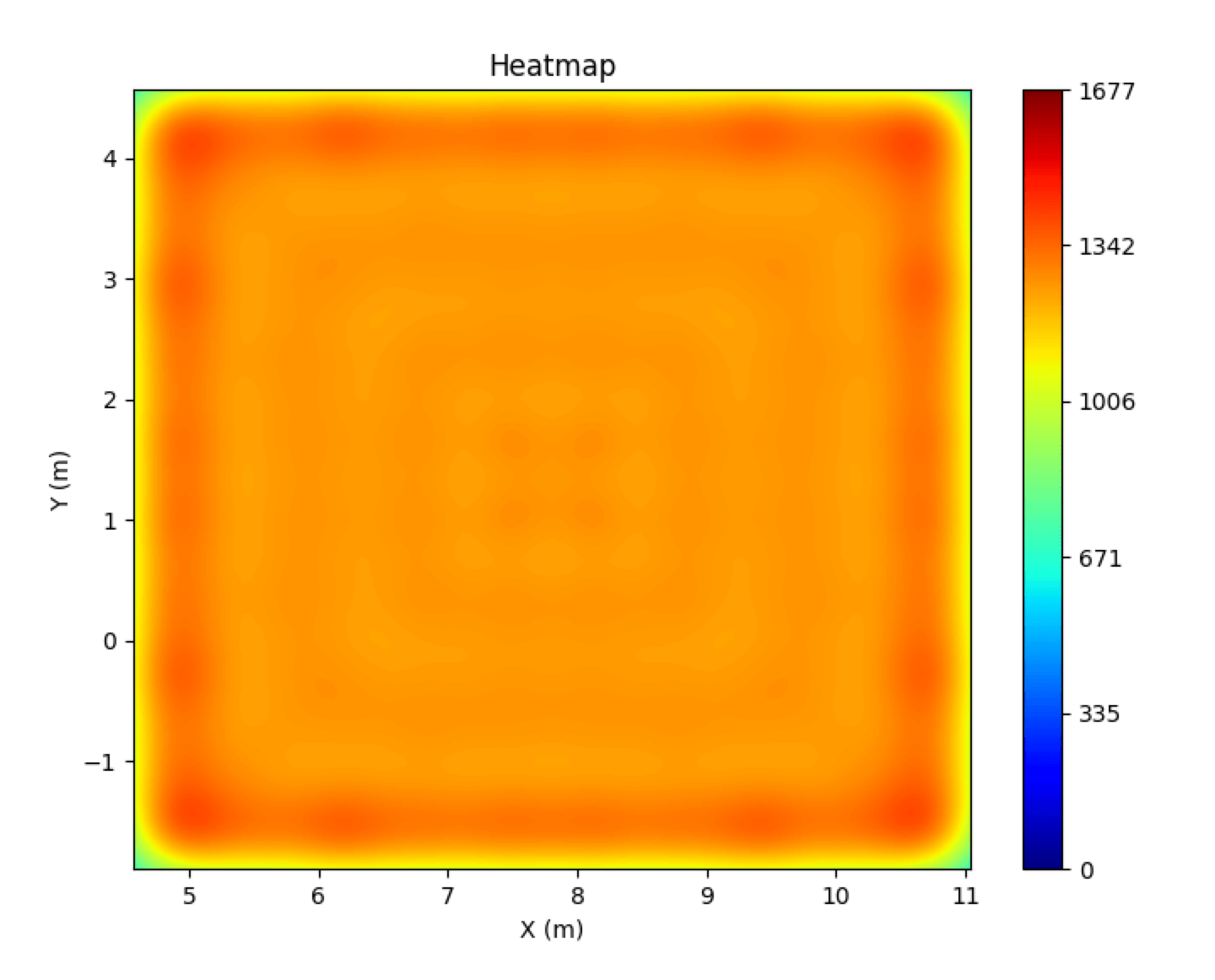

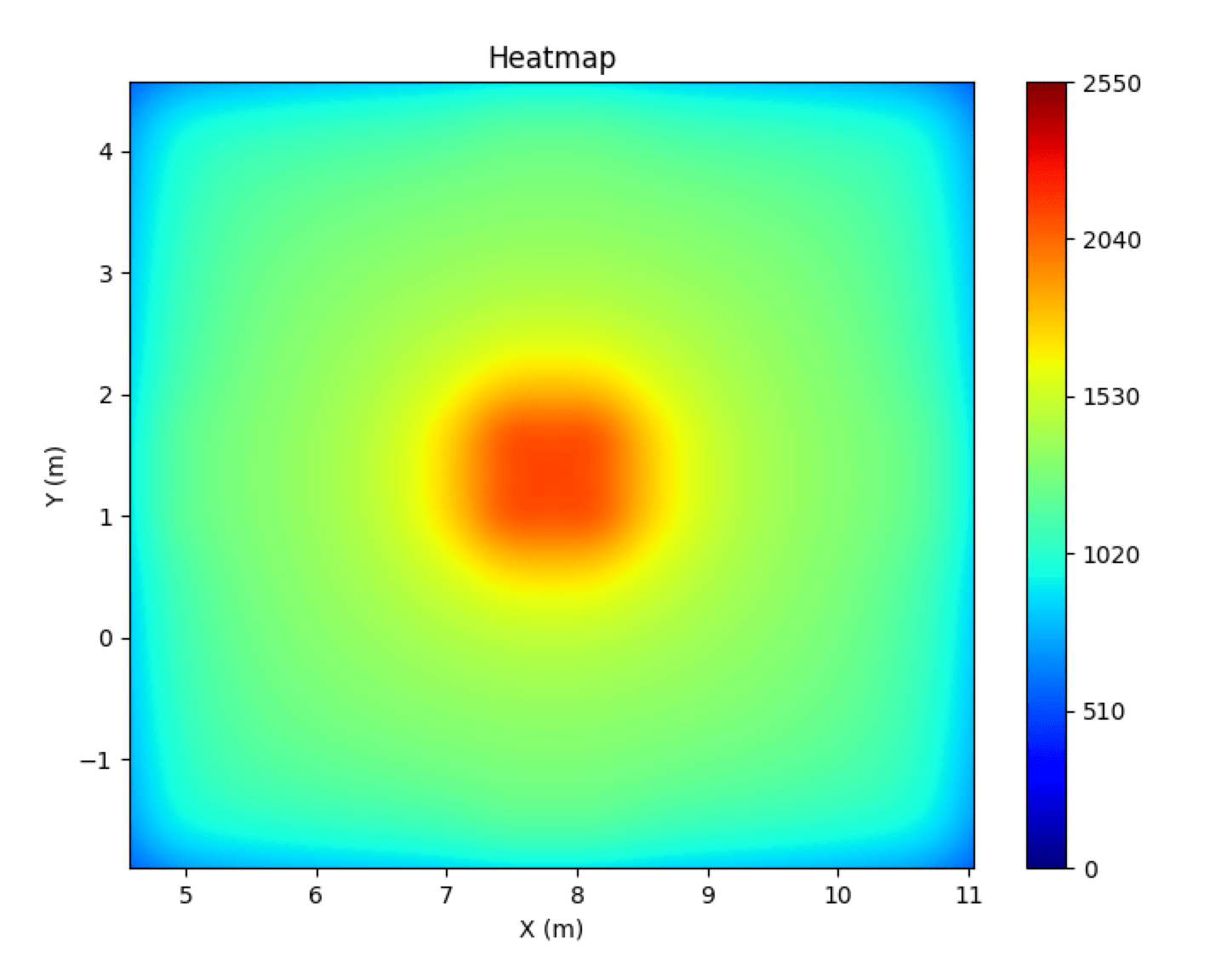

Visualizing Light Uniformity

Below are graphical representations that demonstrate the effectiveness of employing the UPFP in our patented technology to achieve truly uniform light distribution. Each set of graphs offers a simple comparison to highlight our UPFP-based approach. Custom radiosity-based lighting simulation software was written in Python, with the results validated by industry standard tools like DIALux and Radiance lighting simulation software.

Each simulation uses the same centered square sequence pattern arrangement of chip-on-board (COB) LEDs, but the graphs on the right show a simulation where the same luminous flux was applied to each COB LED, while the graphs on the left show intelligent layer-wise luminous flux assignments.

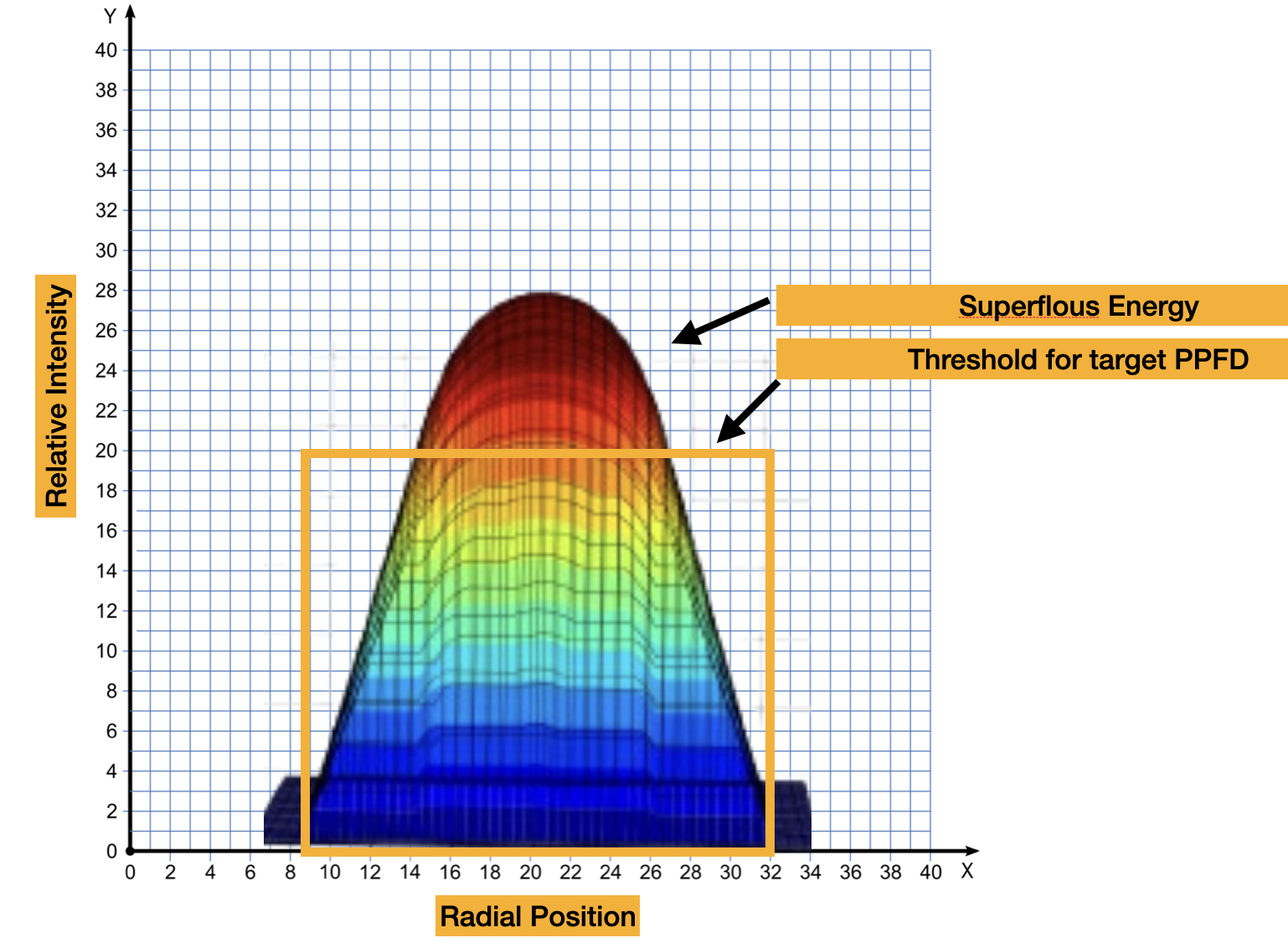

Beam Profile

This side-view of PPFD surface graphs illustrates the spatial distribution of light intensity, highlighting the “superfluous energy” outside the target PPFD range. The UPFP-based graph on the left demonstrates a more uniform beam spread with significantly reduced energy waste.

Figure 1: Comparison of Beam Profiles. Right: Traditional distribution. Left: Optimized UPFP distribution.

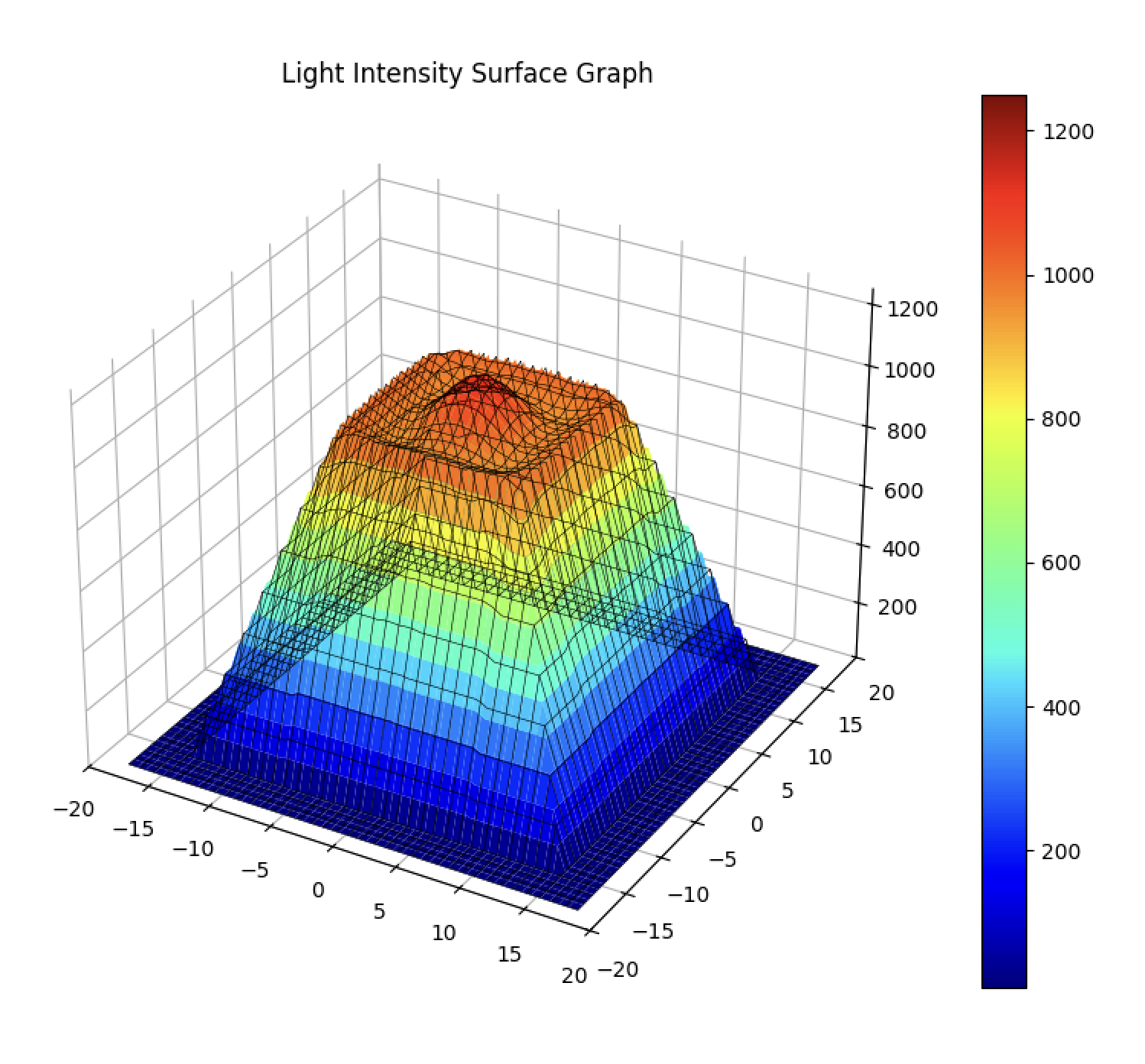

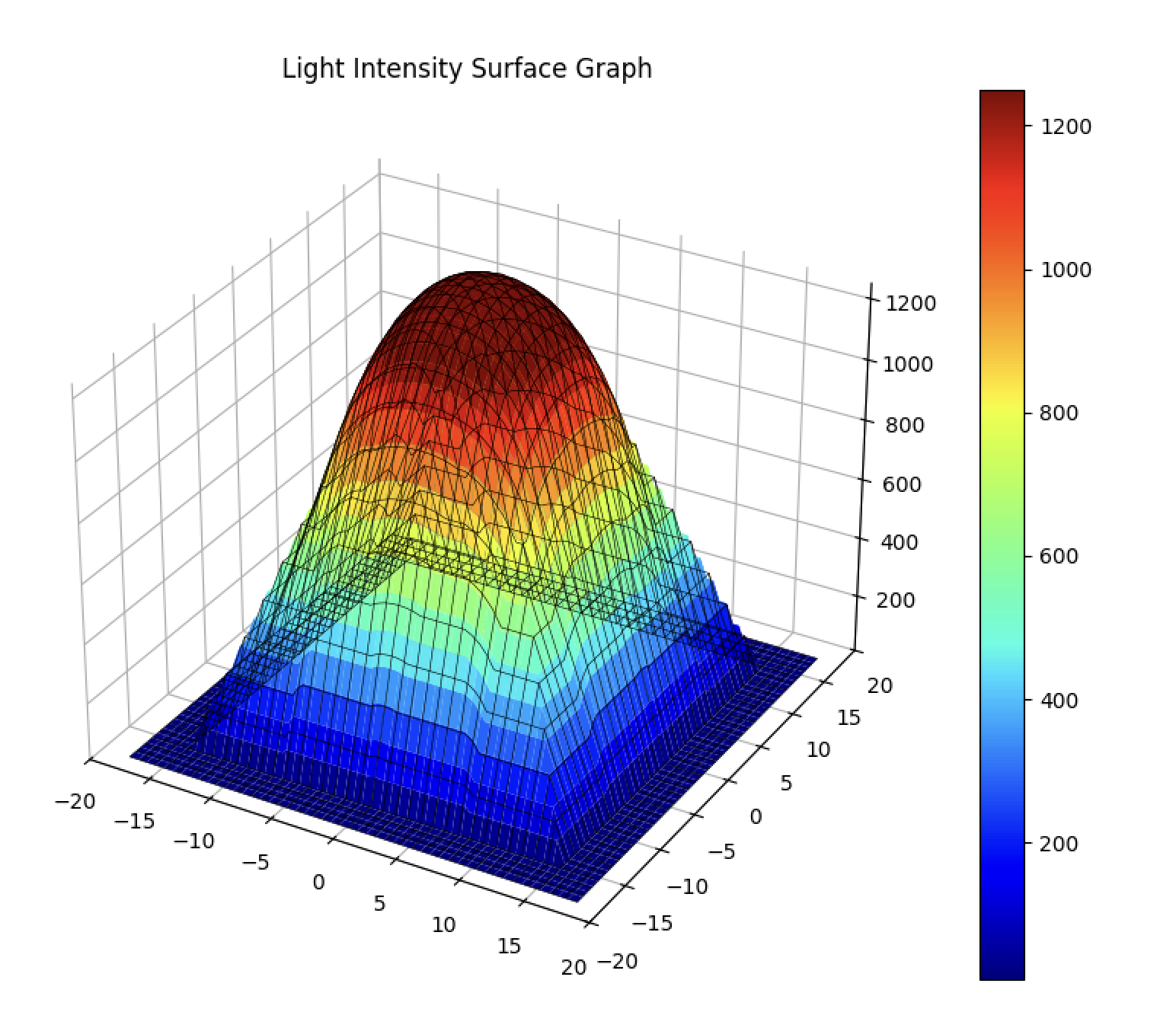

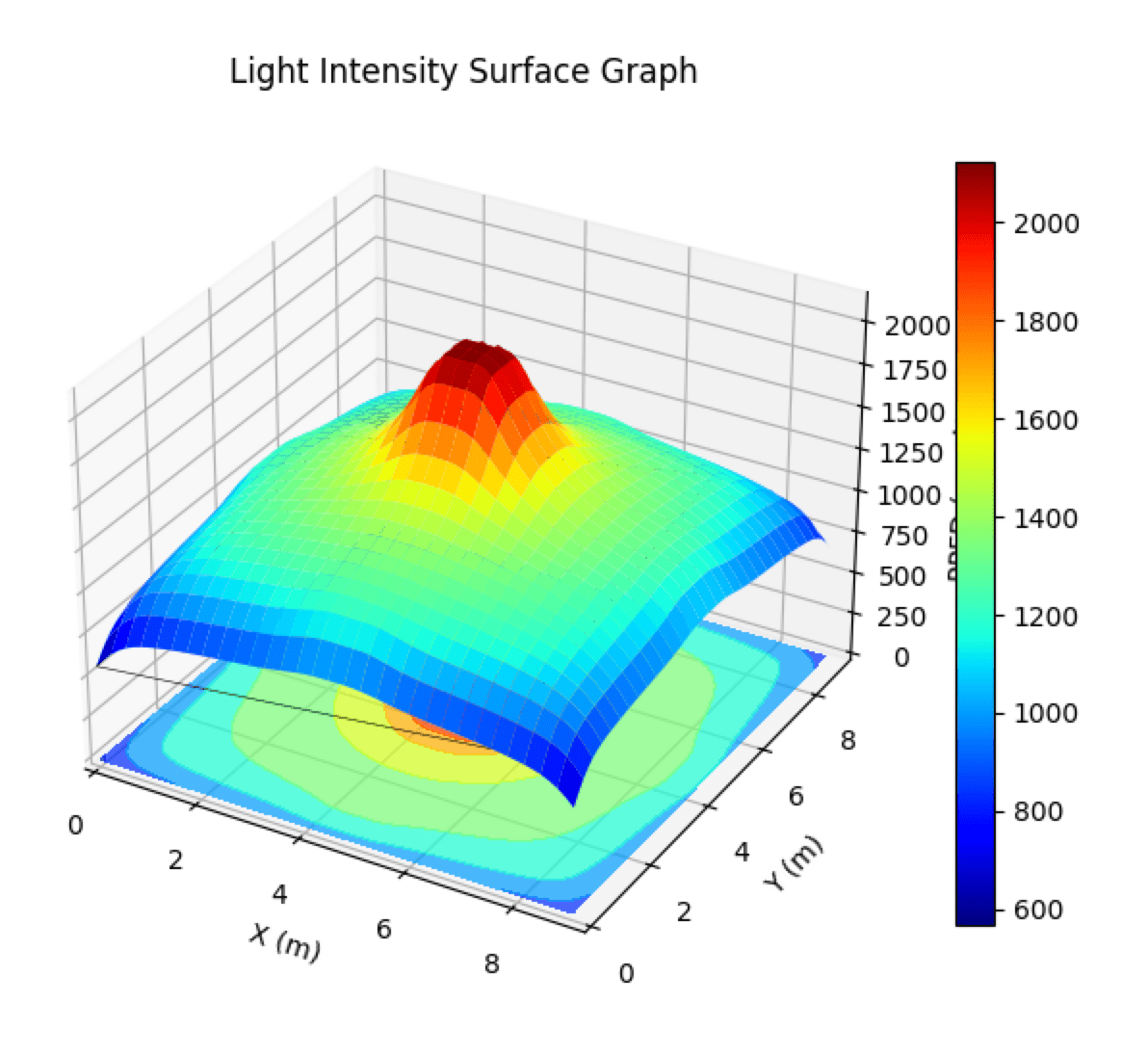

PPFD Surface Graphs

These 3D graphs illustrate the spatial distribution of PPFD, as presented in our research. The colors represent different intensity levels, with blue being low and red being high. The orange square shows the target PPFD range. Note how the UPFP-based graph on the left exhibits a more uniform distribution with minimal “superfluous energy” (light outside the target PPFD range).

Figure 2: Comparison of PPFD Surface Graphs. Right: Traditional distribution. Left: Optimized UPFP distribution.

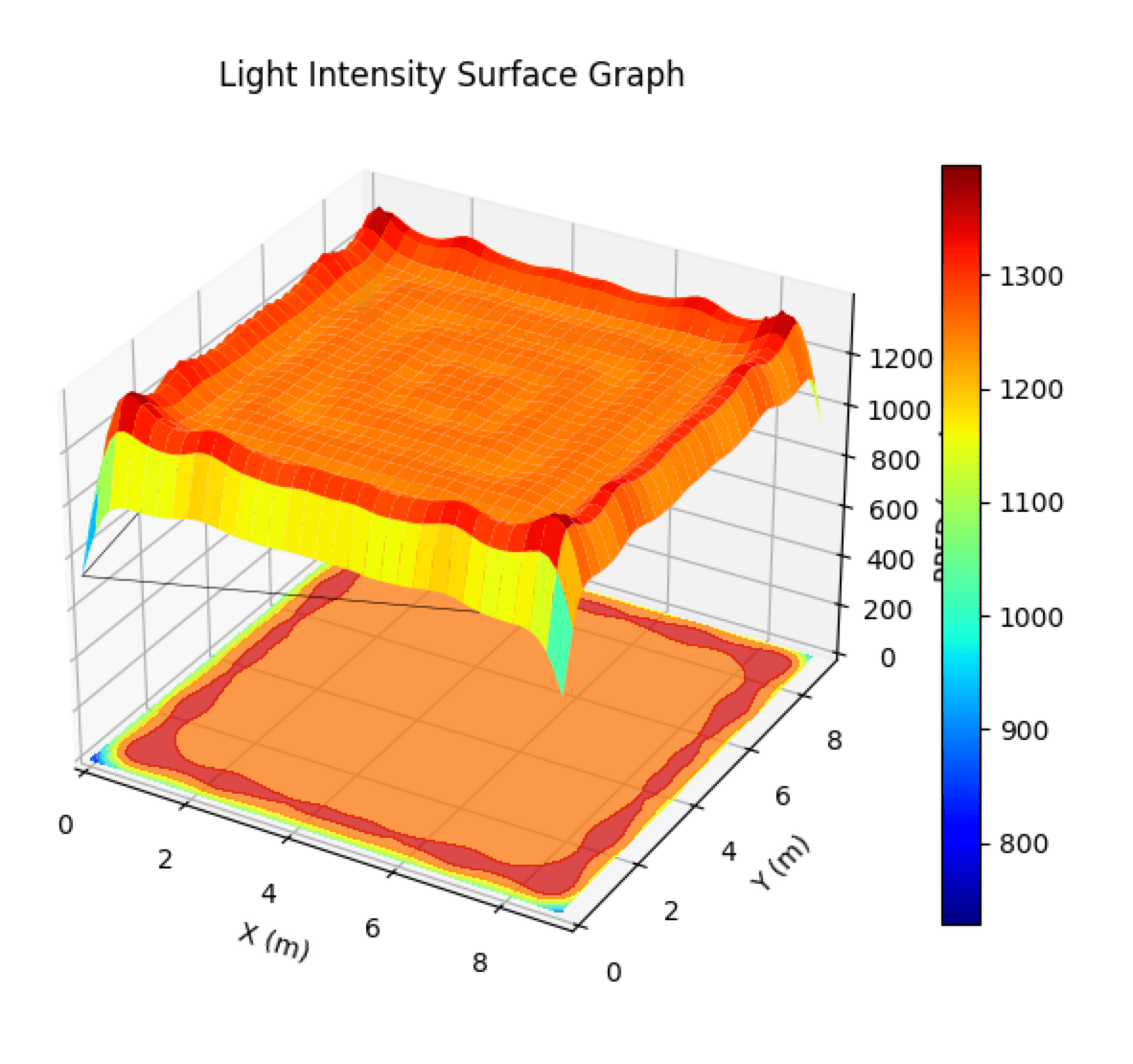

In the surface graphs below, which represent data from a larger floor size of 30′ × 30′ versus the 12′ × 12′ size above, the non-uniformity for the uniform grid matrix of COB LEDs with equal flux is exacerbated, while the UPFP-based methodology maintains high uniformity.

As coverage area increases, saturating that area uniformly becomes more challenging. Our infinitely scalable, modularized approach simplifies this: layer-wise luminous flux assignments for concentric square COB layers solve the uniform saturation problem.

Figure 3: Comparison of 30×30 PPFD Surface Graphs. Right: Traditional distribution. Left: Optimized UPFP distribution.

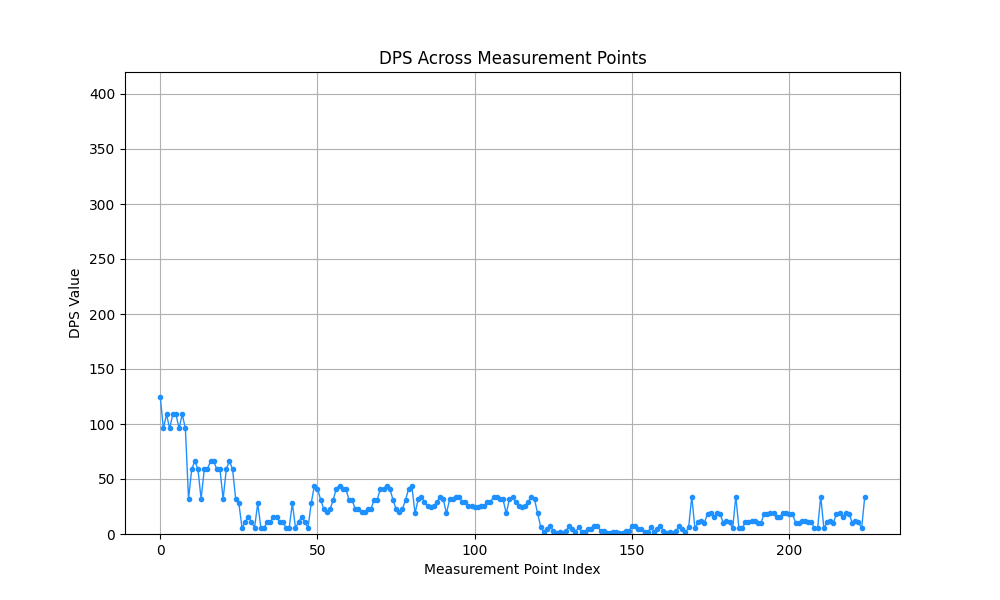

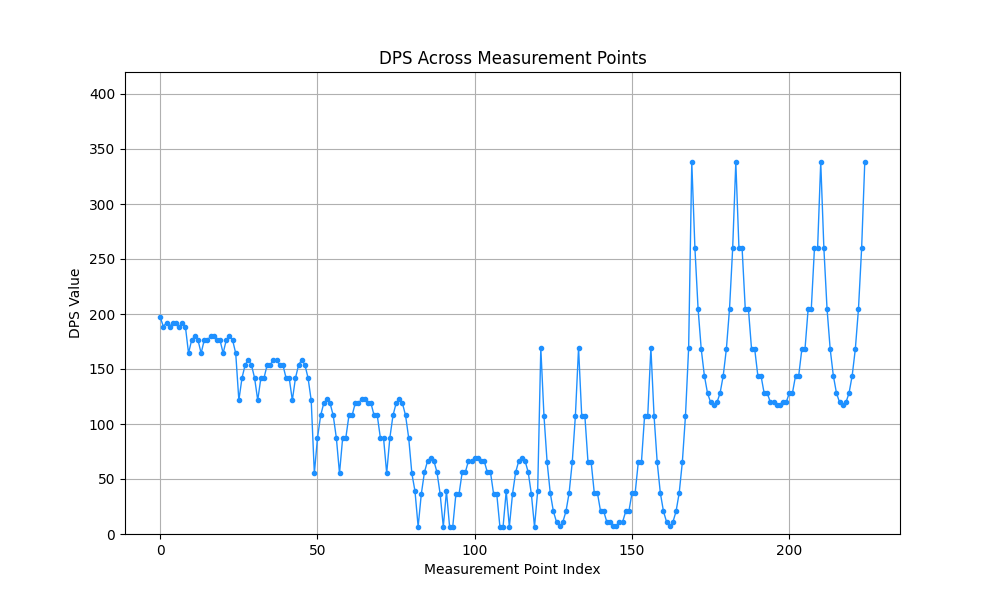

2D Variance Graphs

These graphs provide a top-down view of the PPFD distribution, highlighting variance from the target PPFD. The UPFP-based approach (left) demonstrates significantly reduced variance, showcasing far superior uniformity.

Figure 4: Comparison of 2D Variance Graphs. Right: Traditional distribution. Left: Optimized UPFP distribution.

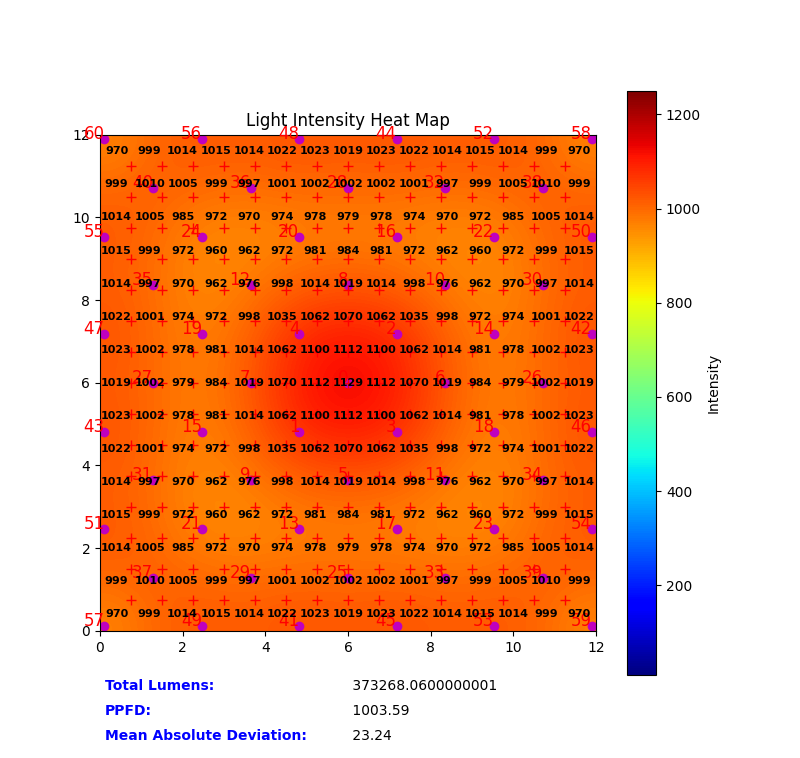

Heatmaps

Heatmaps offer an intuitive way to visualize PPFD distribution. Warmer colors (reds) represent higher PPFD, while cooler colors (blues) represent lower PPFD. The UPFP-based heatmap (left) shows consistent color across the area, signifying superior uniformity. The competitor’s heatmap shows photon concentration at center, seen as a circular pattern.

Figure 5: Comparison of 12′ × 12′ PPFD Heatmaps. Right: Traditional distribution. Left: Optimized UPFP distribution.

Figure 6: Comparison of 30′ × 30′ PPFD Heatmaps. Right: Traditional distribution. Left: Optimized UPFP distribution.

References

Zhang, G., et al., 2015. A combination of downward lighting and upward lighting improves plant growth in plant factories. Hortscience, 50(8), 1126--1130.

Joshi, J., Zhang, G., Shen, S., Supaibulwatana, K., Watanabe, C., Yamori, W., 2017. A combination of downward lighting and supplemental upward lighting improves plant growth in a closed plant factory with artificial lighting. Hortscience 52 (6), 831--835. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI11822-17

Kozai, T., 2022. Role and characteristics of PFALs. Plant Factory Basics, Applications and Advances, 46. Academic Press.

Runkle, E., 2021. Hidden benefits of supplemental lighting. Greenhouse Product News, 42. https://gpnmag.com/article/hidden-benefits-of-supplemental-lighting/